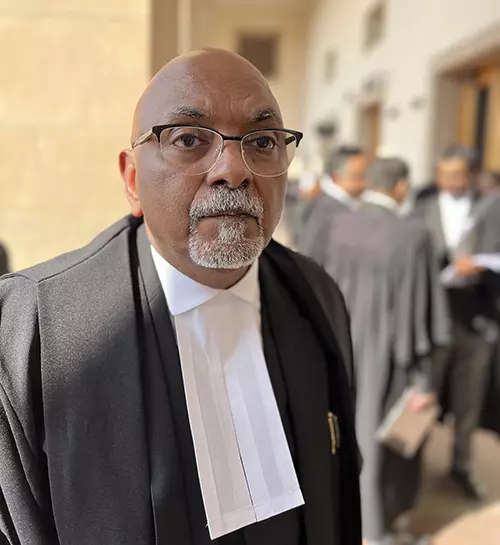

Indira Gandhi's Lawyer From Mauritius

Raju Ramachandran , Senior Advocate

7 May 2025 8:03 AM

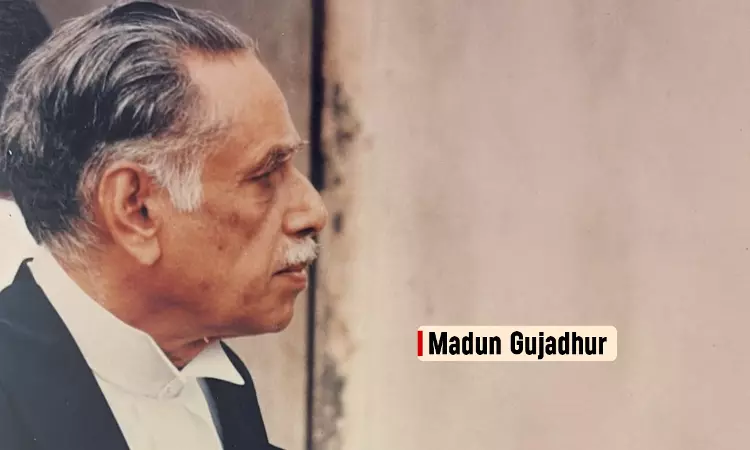

As the 50th anniversary of the Emergency looms next month, my mind goes back to the fast paced legal developments starting from 12th June, 1975, which led to the Proclamation of the Emergency on the 25th of June. In that legal drama which unfolded, one of the lawyers of Indira Gandhi, a Mauritian barrister named Madun Gujadhur has not received sufficient notice.On the 12th of June 1975, a...

As the 50th anniversary of the Emergency looms next month, my mind goes back to the fast paced legal developments starting from 12th June, 1975, which led to the Proclamation of the Emergency on the 25th of June. In that legal drama which unfolded, one of the lawyers of Indira Gandhi, a Mauritian barrister named Madun Gujadhur has not received sufficient notice.

On the 12th of June 1975, a Single Judge of the Allahabad High Court, Justice Jagmohan Lal Sinha delivered his historic judgment setting aside the election of Indira Gandhi from Rae Bareli in 1971 on grounds of corrupt practice.

It was the summer vacation both for the Supreme Court and for the Delhi University. I was in transition from my second year to the third year of my law course at the faculty of law and was keenly following the course of the case.

Justice Sinha, in keeping with legal precedent, stayed his verdict for a period of 20 days to enable Indira Gandhi to file her statutory appeal to the Supreme Court. Indira Gandhi chose N.A. Palkhivala to be her lead counsel in the Supreme Court, and he promptly accepted the engagement.

This was a tribute to both. Indira's socialist government had faced several legal reverses in the Supreme Court in battles spearheaded by Palkhivala. These include the Bank Nationalisation case, the Privy Purses case, and finally the “basic structure” case (Kesavananda Bharati). She saw the formidable professional acumen of Palkhivala.

Equally, Palkhivala, who was not just a formidable lawyer but a torch bearer of capitalism, was ultimately a legal professional in the finest sense. Palkhivala understood that the election of the Prime Minister could not have been set aside on the flimsy ground of “misuse” of government jeeps or helicopters, and he immersed himself in the case.

On 24th June 1975, the socialist judge, Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer, going strictly by judicial precedent passed a conditional stay order overruling Palkhivala's contention that an absolute stay was called for. The High Court's judgment and her consequent disqualification were stayed on the condition that she could attend the House, sign the register, but not vote, speak or draw her salary as an MP. She could however function as the Prime Minister and could speak in the House as the Prime Minister.

Armed with this order of stay, Indira Gandhi proclaimed the Emergency the very next day, on 25th June. Palkhivala promptly withdrew from her case and a new legal team had to be put together. This is where the subject of the present article comes in.

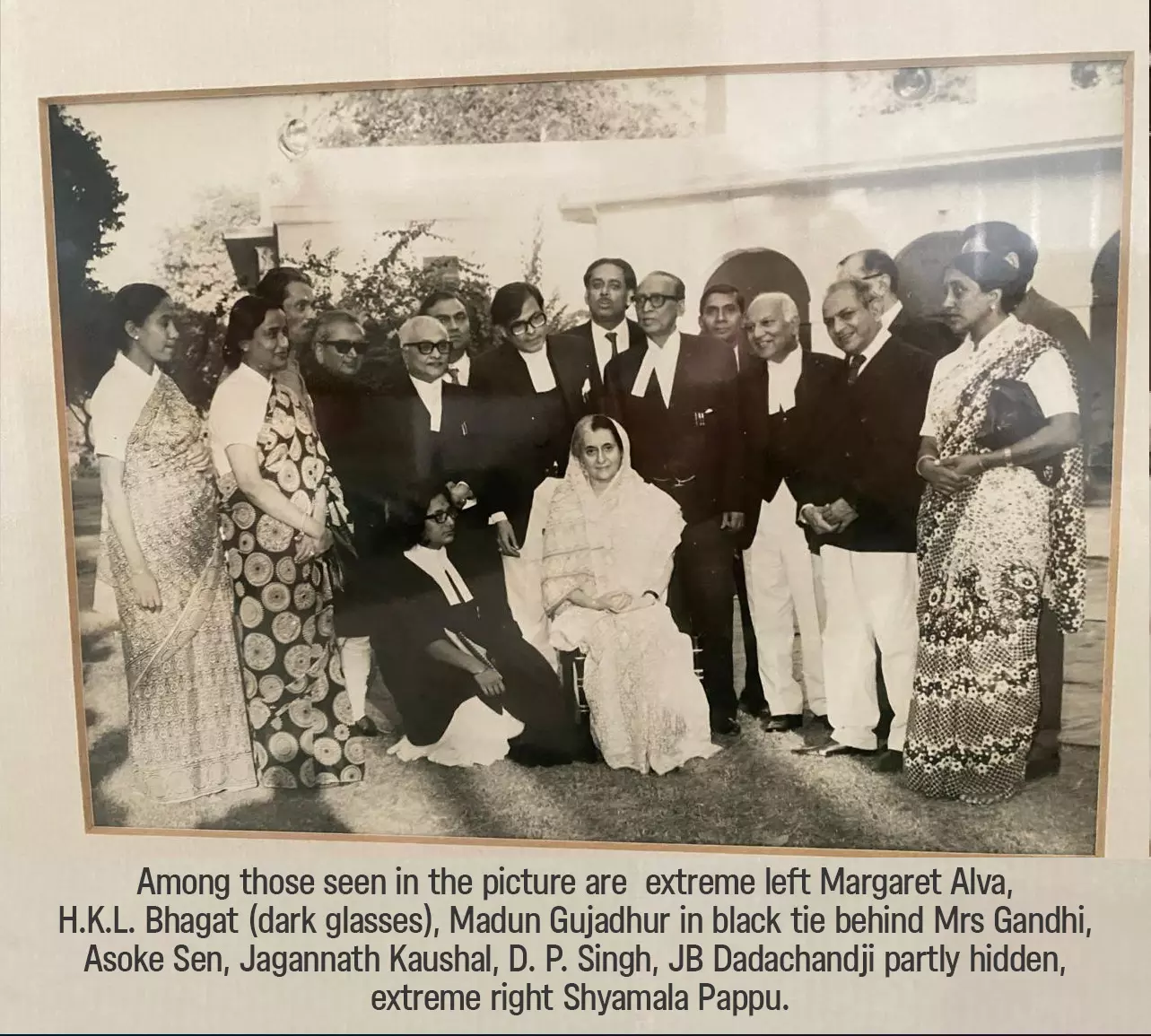

Asoke Kumar Sen now became the lead counsel. Sen was a formidable counsel and had been Law Minister in the Nehru and Shastri cabinets. The team included well-known Congress lawyers, D.P. Singh, Jagannath Kaushal and H.K.L. Bhagat. But what intrigued me were the reports in the newspapers that a lawyer called Madun Gujadhur from Mauritius was being drafted into the team. The name has stayed with me since then.

For the record, Indira Gandhi's election was saved by a retrospective amendment to the Representation of People's Act which the Supreme Court applied. However, the Constitution Thirty Ninth Amendment Act, 1975 which put the election of a Prime Minister beyond the pale of judicial scrutiny was struck down by applying the newly minted basic structure doctrine.

In the meantime, I had become a lawyer and it was in 1996 that a young Aparajita Singh joined the Bar (she is now a senior counsel herself and a very dear friend). She introduced me to her parents, and I remember her late father telling me that she had been inspired to become a lawyer because of the example set by her uncle, Madun Gujadhur.

So here was a person from whom I could know more about this hitherto mysterious individual. He became more and more fascinating, as I got to know about him over the years.

Madun Mohan Gujadhur was born in Mauritius in 1927 to Ackbar Gujadhur who was himself a lawyer. Ackbar Gujadhur was the son of Rajcoomar Gujadhur, a wealthy sugar planter, owner of race horses and a Member of the Legislative Council of Mauritius.

After his primary and secondary education in Port Louis, Gujadhur went to the Royal College Curepipe, where he studied Greek and Latin as well (Incidentally, Curepipe was the hometown of another Mauritian barrister family, the Goburdhuns, who moved to India to practice law. A descendent of that family, Devendra Goburdhun is now a Senior Advocate of the Supreme Court).

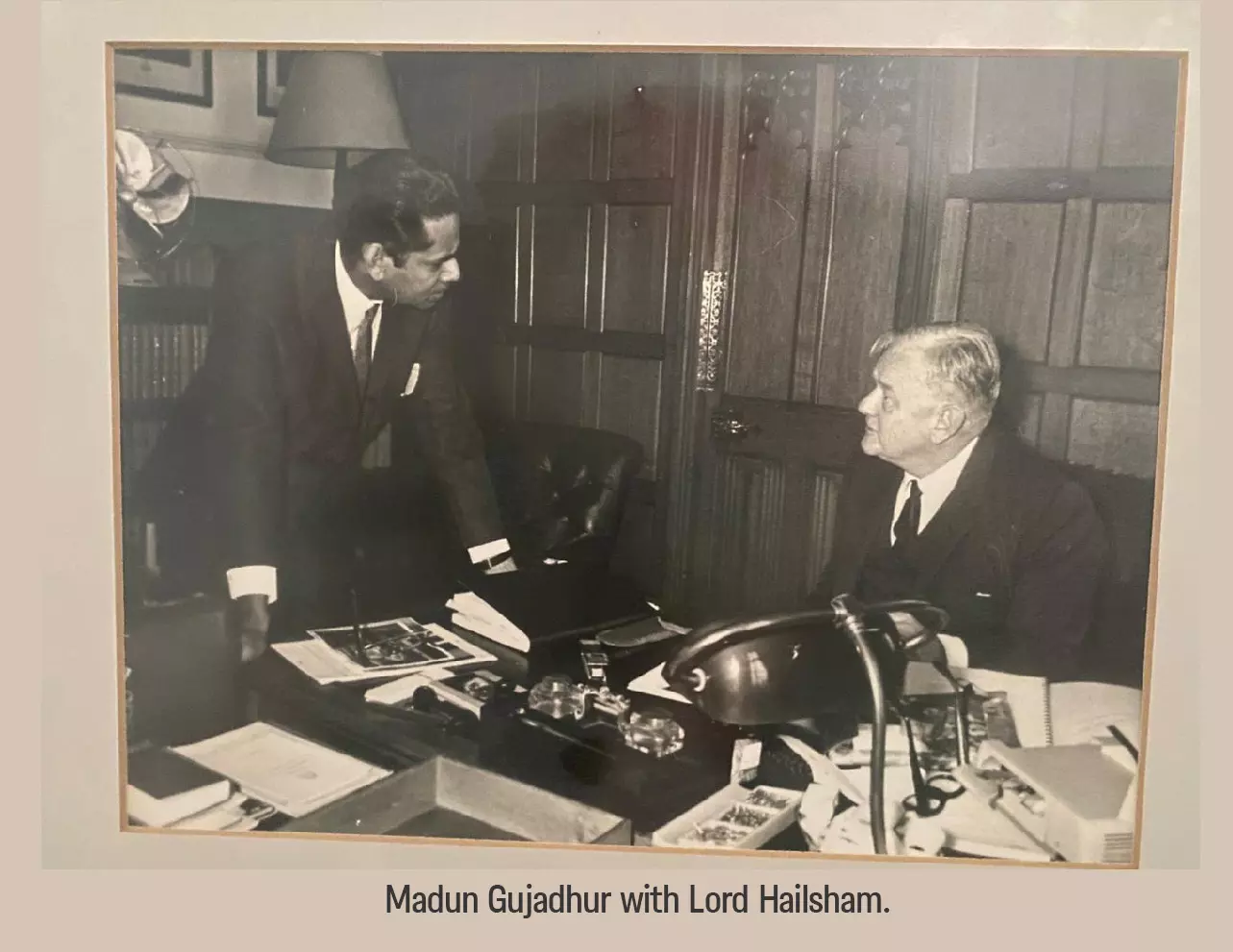

Gujadhur then moved to London, where he was called to the Bar in 1952 from the Middle Temple. He “devilled” in the Chambers of the iconic Quintin Hogg who later became Lord Hailsham of Saint Marylebone, the Lord Chancellor of England.

Instead of staying on in England, Gujadhur decided to discover his roots in India. In his own words “Then came my greatest piece of luck. I married in India and my father suggested that I should practice law in India”. He started practice in the Patna High Court in the chambers of Lal Narayan Sinha, who later was Indira Gandhi's Solicitor General and Attorney General successively.

On of the significant cases he argued was for the editor of the Searchlight newspaper against his senior who represented the State. On his association with Lal Babu (as Lal Narayan Sinha was known) Gujadhar later wrote “I learnt much. I learnt to question.”

It was during this period that a triumvirate of the three promising young lawyers, Gujadhur, Lalit Mohan Sharma and Akbar Imam made their mark. They remained lifelong friends (Akbar Imam passed away prematurely in 1967).[1] Lalit Mohan Sharma went on to become Chief Justice of India.

Gujadhur assisted Lal Babu when he argued the famous Golak Nath case (1967) as the Advocate General of Bihar that. It was here the Supreme Court held for the first time, that the power of Parliament to amend the Constitution did not extend to curbing Fundamental Rights. This led to a bitter constitutional battle, culminating in the Kesavananda Bharati case in 1973, which held that every part of the Constitution could be amended but its basic structure could not be destroyed. On Lal Babu's preparation in Golak Nath Gujadhar wrote “His greatest forensic achievement to my mind was when he anticipated months ahead, Palkhivala's arguments on the amendability of the Indian constitution.”

It is the quality of assistance given by Gujadhur in Golak Nath that made Lal Babu think of him some years later and recommend him to Indira Gandhi for her personal legal team. This meant calling him from Mauritius as he had to return home to take over the family responsibility on his father's death.

When Gujadhur returned to Mauritius after helping in the preparation of the election case, Lal Narayan Sinha as Solicitor General took the unusual step of writing to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to put on record his valuable contribution to the case. He said “I have taken the unusual course of writing to you, because I thought that the Prime Minister of Mauritius and the Union of Mauritian Socialist Lawyers should know the high esteem and appreciation we have for our colleague and the hard work he has put into the preparation of the case. His approach to the case is deeply influenced by his unconditional acceptance of the justice of the cause argued… I had never treated Madun Gujadhur as a 'foreigner' and his entire outlook is to use his own words 'metropolitan Indian'.”

A year after Indira Gandhi's case was decided, Madun Gujadhur was made Queen's Counsel in Mauritius in 1976. Mauritius, which gained Independence in 1968, became a republic only in 1992. Having been associated, as a senior constitutional lawyer, with the transition of his country to a republic, he was commissioned by the Republic Advisory Committee of Australia which was constituted by the then Australian Prime Minister, Paul Keating to examine the constitutional and legal issues which would arise were Australia to become a republic. Gujadhur had acquired the stature of a Commonwealth constitutional lawyer.

In reminiscences recorded by Ravi Visvesvaraya Prasad, son of Indira Gandhi's legendary information advisor H.Y Sharada Prasad, Gujadhur is credited with two important roles, apart from working on the election case. It appears, and this is common knowledge from those times, that Indira Gandhi had seriously toyed with the idea of switching over to a presidential form of government. Gujadhur was tasked with sounding out Lords Denning and Hailsham about the proposal. He got back to her, telling her of their view that if such a thing were to happen, India risked losing membership of the Commonwealth.

Ravi Prasad also makes the conjecture that it was the advice of the legal stalwart J.B Dadachandji and Madun Gujadhur which might have been a factor in Indira Gandhi, ending the Emergency.

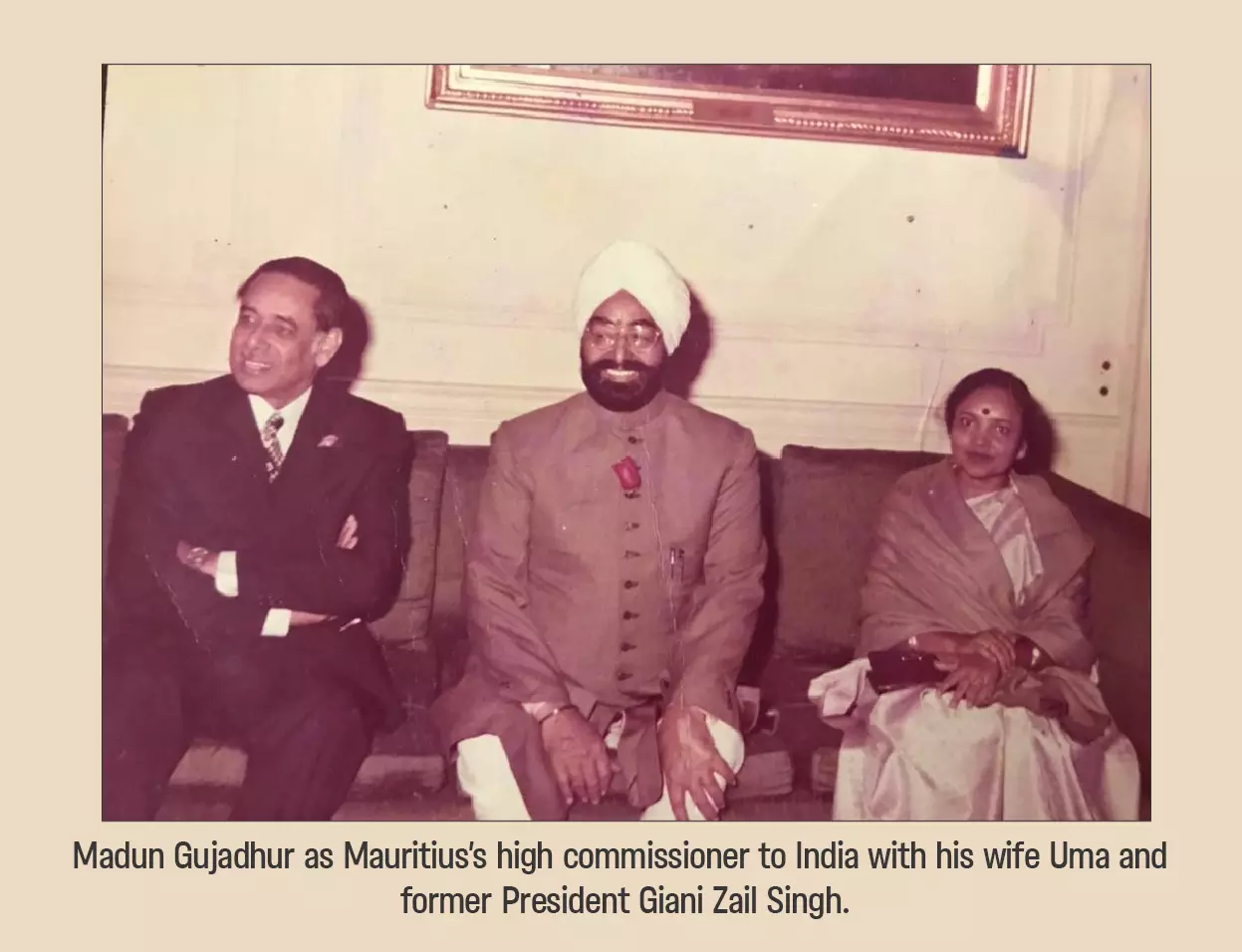

Gujadhar held many distinguished positions in his country. He was Chairman of the Law Reform Commission and was also Chairman of the Mauritius Broadcasting Corporation. He commanded a lucrative legal practice, but his love for India brought him back to Delhi as the High Commissioner of his country for a brief period from November 1982 - June 1983.

In one of his writings he mused “I feel now I have seen the heart of India beat, I have felt the caress of the Indian people's affection. Now, I realise the poignancy of Jawaharlal's words, when he cried that he felt nowhere at home. Only two generations separate me from the brethren I knew in India. Can the generations really separate?”

Gujadhar passed away on 5th May, 1995, thirty years ago but the stories continue . On his passing, Sir Marc David, QC and a doyen of the Mauritius Bar wrote “Stalwart, fearless, preoccupied with the notions of liberty and fundamental rights, Madun never hesitated to stand unflinchingly for his clients' welfare and the dignity of the bar.”

Another friend Deepchand Beeharry, a renowned Mauritian writer wrote “Madun Gujadhur was not only an intellectual giant but also had a heart of gold. He was equally at home with Shakespeare, Molière and could with equal ease recite quotations from Iqbal, Mahadevi Varma, Julius Caesar or Jayshankar Prasad."

Sir Marc, also agreed saying “Equally at ease in English, French, Hindi and Urdu, he had the wonderful talents of communication and dialectics which went with an incisive mind, a disarmingly quizzical and tongue-in-cheek approach, a sharp, sometimes even caustic, wit and thought-provoking banter to which was suited his drawling voice. Many an earnest word he said in jest. He was in his inexhaustible fund of witticisms and his well-timed parting shots. Indeed, his excellent memory served him in good stead.”

A classic example of Gujadhur using language to further the cause of his client happened in the Patna High Court. In a case badly marred by limitation, his client could not explain the last four days despite copious pleadings in Trial Court. Asked to explain by the Court, Gujadhur urged “Huzoor, do Arzoo mein kat gaye, do intezaar mein” ( My Lord, two passed away in yearning and two waiting). Justice S.C. Mishra was so impressed by a Mauritian quoting Zafar that he promptly issued notice.

Aparajita Singh fondly remembers: 'For us he was the uncle whom the entire clan surrounded every time he visited Patna. As children we knew he was a “big lawyer” but his unassuming manner (catching a rickshaw to visit his friend and relative Justice L M Sharma) and happy banter with the young and old put everyone at ease. It was only in 1980 when I saw Prime Minister Indira Gandhi at his daughter's wedding in Delhi that I realized that he was an “important” man.'

The writer is a Senior Advocate, Supreme Court of India. Views are personal.

The article is a modified version of the article published in The Wire.

[1] Raju Ramachandran, The Lawyer Who Made Flying Visits To Courts (LiveLaw.in, 19th Aug 2024) available at :- https://www.livelaw.in/articles/bihar-lawyer-akbar-imam-flying-plane-for-court-visits-266394.